Executive Summary

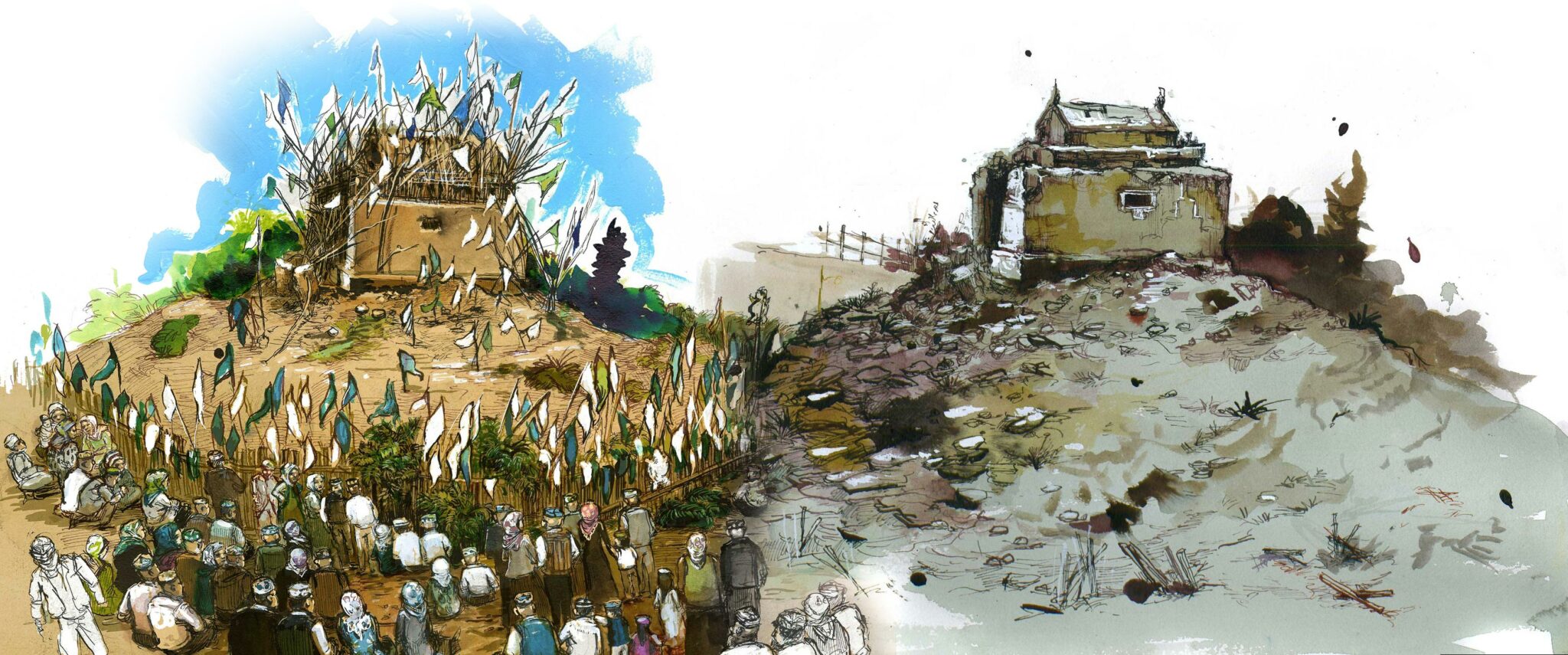

Since 2017, under the guise of a campaign against “terrorism”, the government of China has carried out massive and systematic abuses against Muslims living in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang). Far from a legitimate response to the purported terrorist threat, the government’s campaign evinces a clear intent to target parts of Xinjiang’s population collectively on the basis of religion and ethnicity and to use severe violence and intimidation to root out Islamic religious beliefs and Turkic Muslim ethno-cultural practices. The government aims to replace these beliefs and practices with secular state-sanctioned views and behaviours, and, ultimately, to forcibly assimilate members of these ethnic groups into a homogenous Chinese nation possessing a unified language, culture, and unwavering loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

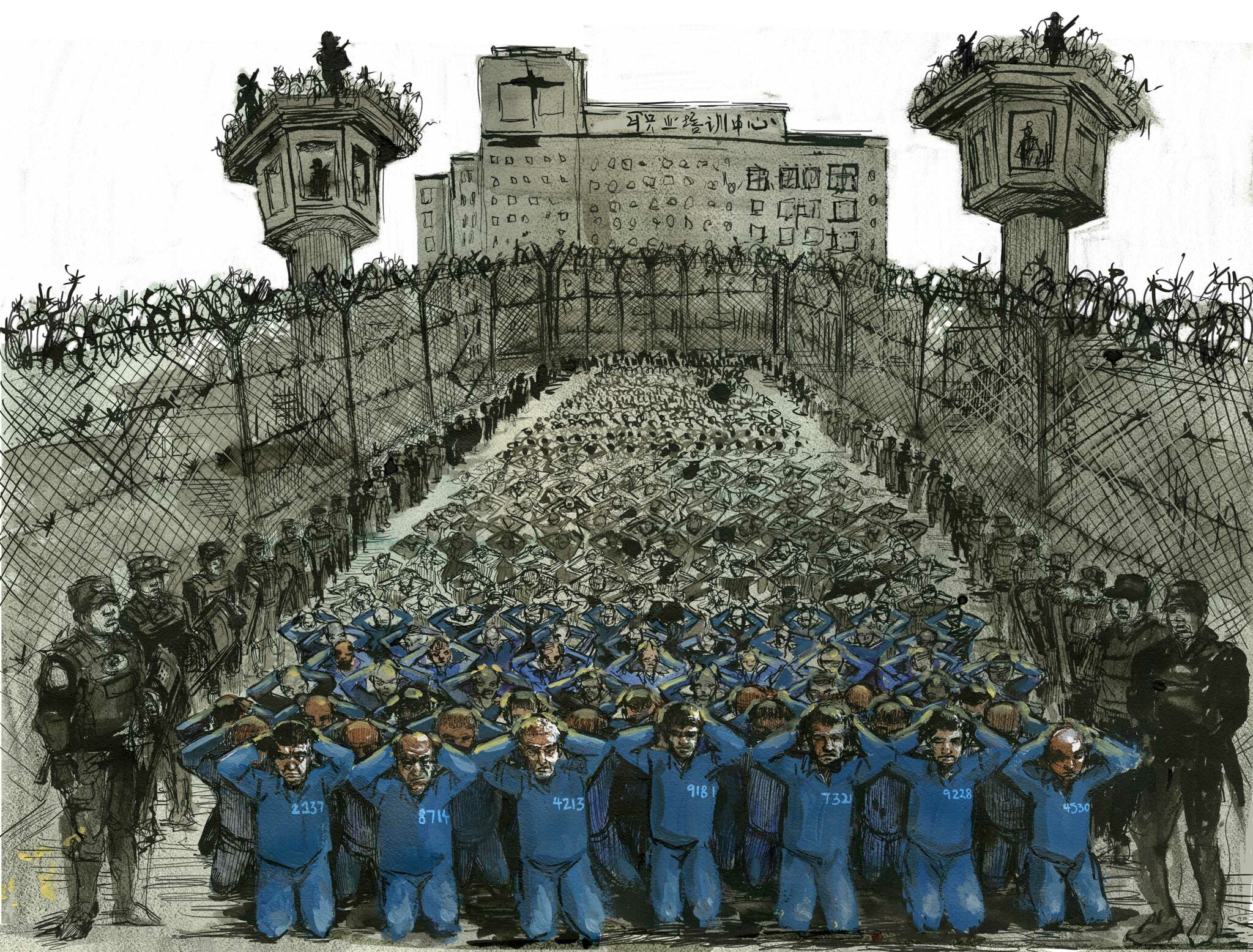

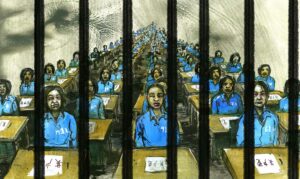

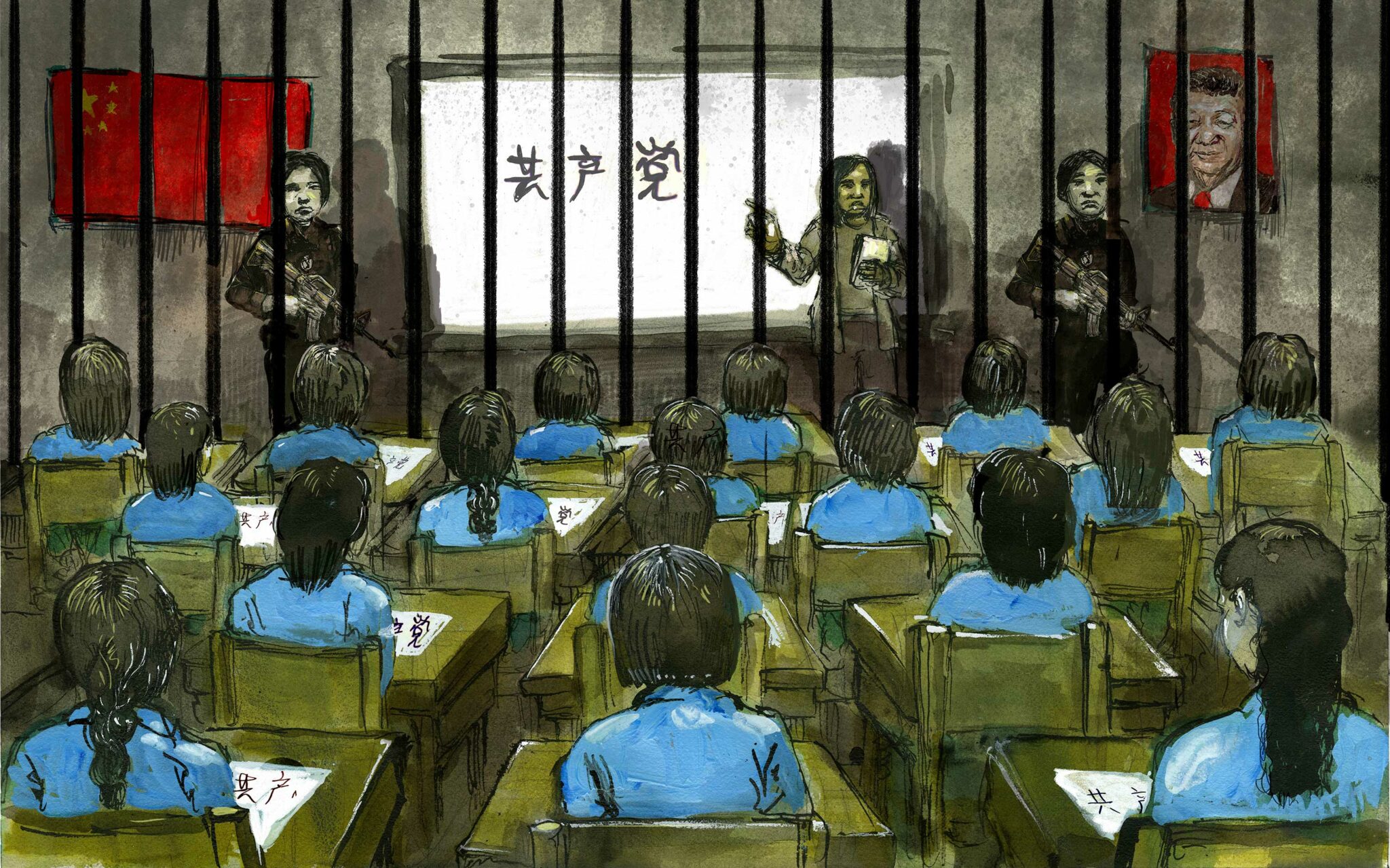

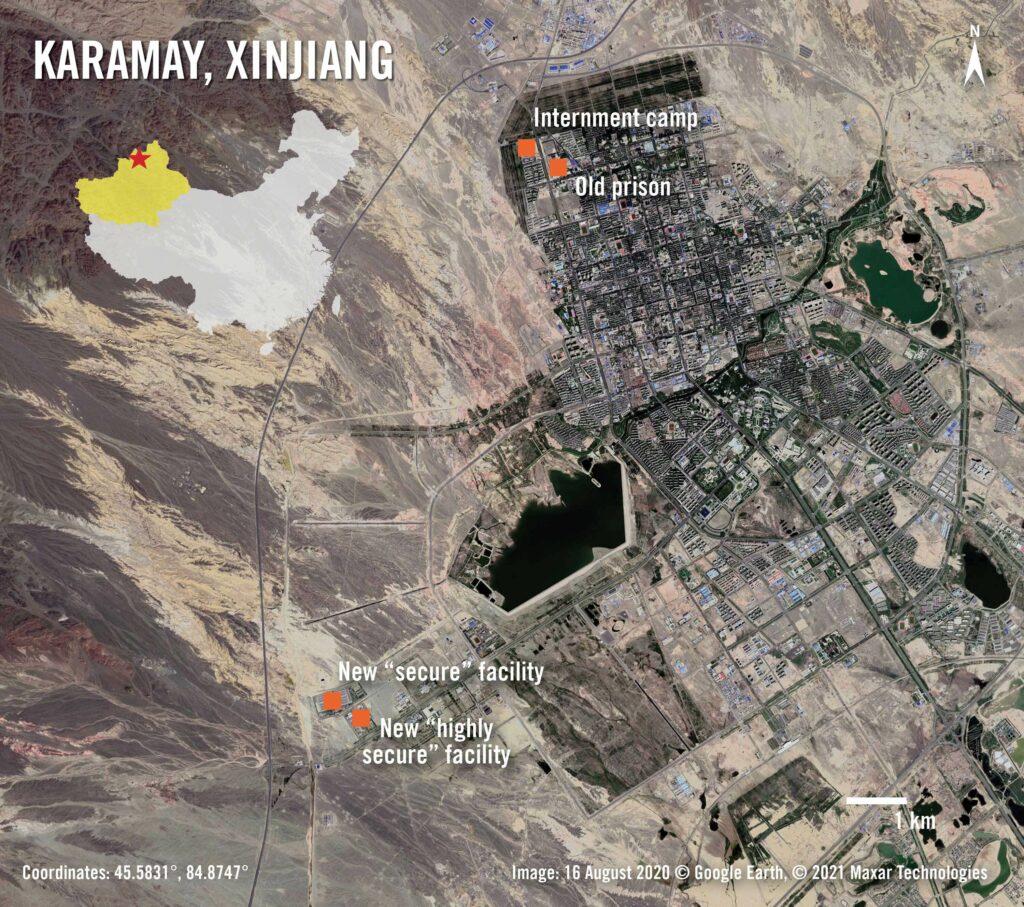

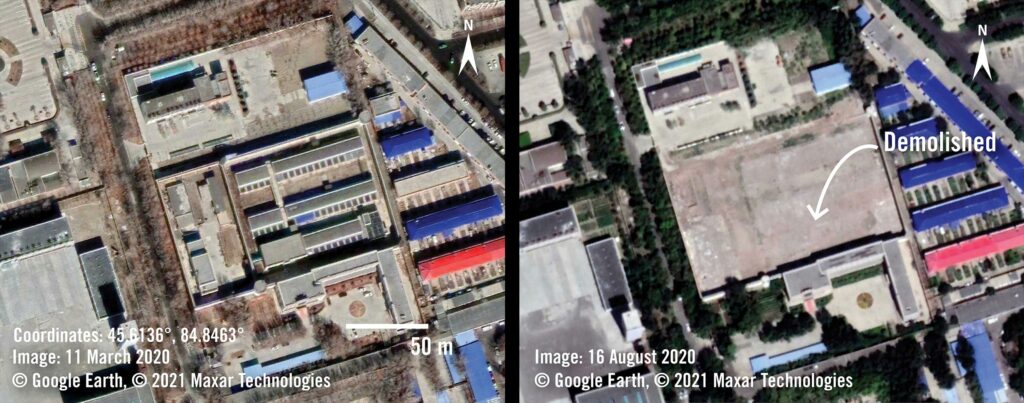

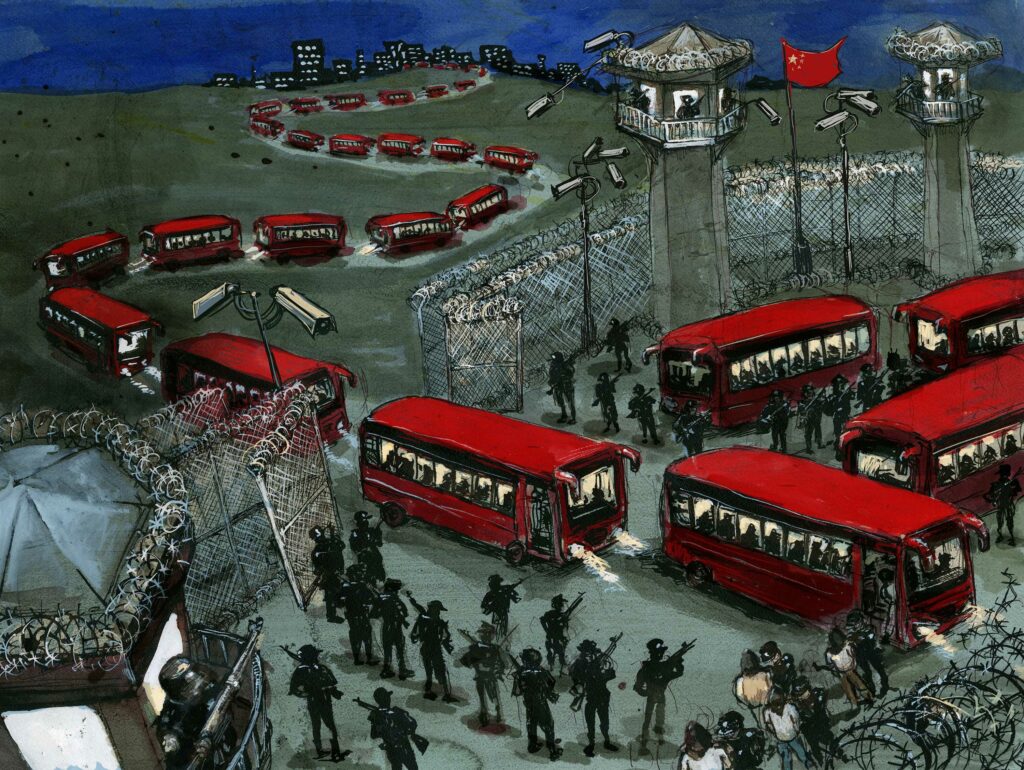

To achieve this political indoctrination and forced cultural assimilation, the government undertook a campaign of arbitrary mass detention. Huge numbers of men and women from predominantly Muslim ethnic groups have been detained. They include hundreds of thousands who have been sent to prisons as well as hundreds of thousands – perhaps 1 million or more – who have been sent to what the government refers to as “training” or “education” centres. These facilities are more accurately described as internment camps. Detainees in these camps are subjected to a ceaseless indoctrination campaign as well as physical and psychological torture and other forms of ill-treatment.

The internment camp system is part of a larger campaign of subjugation and forced assimilation of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang. The government of China has enacted other far-reaching policies that severely restrict the behaviour of Muslims in Xinjiang. These policies violate multiple human rights, including the rights to liberty and security of person; to privacy; to freedom of movement; to opinion and expression; to thought, conscience, religion, and belief; to participate in cultural life; and to equality and non-discrimination. These violations are carried out in such a widespread and systematic manner that they are now an inexorable aspect of daily life for millions of members of predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

The government of China has taken extreme measures to prevent accurate information about the situation in Xinjiang from being documented, and finding reliable information about life inside the internment camps is particularly difficult. Between October 2019 and May 2021, Amnesty International interviewed dozens of former detainees and other people who were present in Xinjiang since 2017, most of whom had never spoken publicly about their experiences before. The testimonies of former detainees represent a significant portion of all public testimonial evidence gathered about the situation inside the internment camps since 2017.

The evidence Amnesty International has gathered provides a factual basis for the conclusion that the Chinese government has committed at least the following crimes against humanity: imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law; torture; and persecution.

Amnesty International interviewed 55 people who had been detained in internment camps and later released. All of them had been arbitrarily detained for what appears to be, by all reasonable standards, entirely lawful conduct; that is, without having committed any internationally recognized criminal offence. The internment camp detention process appears to be operating outside the scope of the Chinese criminal justice system or other domestic law. According to government documents and statements by government officials, applying criminal procedure would be inappropriate because the people in the camps are there “voluntarily” and are not criminals. As demonstrated by the testimonies and other evidence presented in this report, however, attendance in the camps is not voluntary, and conditions in the camps are an affront to human dignity.

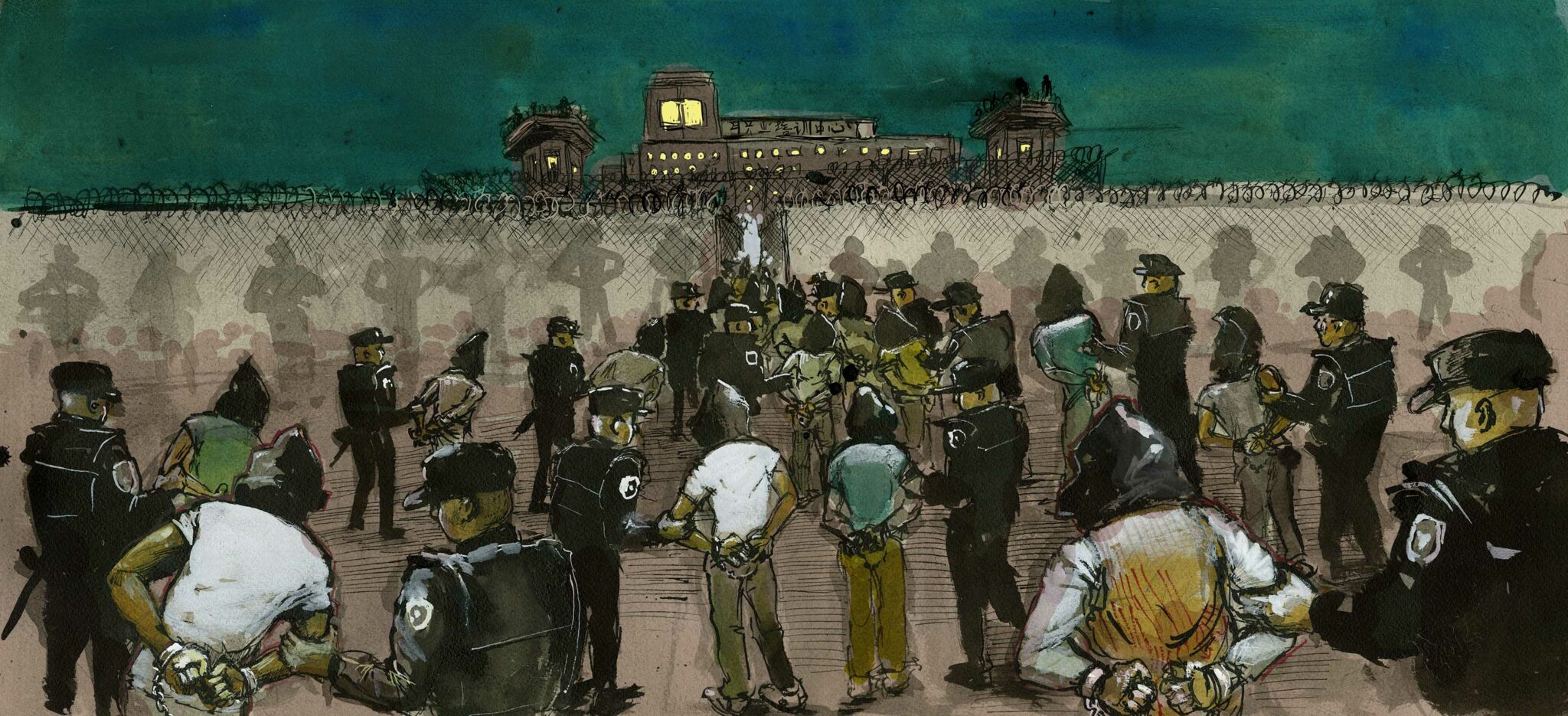

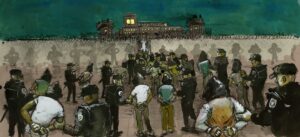

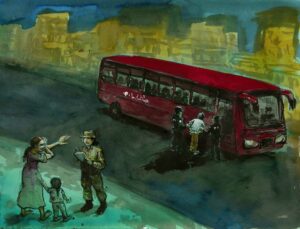

Aiman, a government official who participated in mass arrests, told Amnesty how, in late 2017, police took people from their homes without warning, how family members of the detained people reacted, and what the role of government cadres was in the process:

I was there… The police would take people out of their houses… with hands handcuffed behind them, including women… and they put black hoods on them… Nobody could resist. Imagine if all of a sudden a group [of police] enters [your home], cuffs you and puts [a black hood] over your head… It was very sad… [Afterwards] I cried… That night we made 60 arrests… That was just in one district [of many where people were being detained]… Every day they arrested more people.

Individuals Amnesty International interviewed said the reasons they were given for their detention were often not tied to specific acts; rather, detainees were informed that they had been detained because they had been classified as “suspicious” or “untrustworthy” or as a “terrorist” or an “extremist”. When specific acts were mentioned, they generally fell into a few broad categories. One category includes offences related to foreign countries. Numerous former detainees were sent to camps for living, travelling, or studying abroad or for communicating with people abroad. Many were even detained simply for being “connected” with people who lived, travelled, studied, or communicated with people abroad. Another category includes those detained for offences related to using unauthorized software or digital communications technology. Many former detainees were sent to camps for using or having forbidden software applications on their mobile phones. Another common category includes anything related to religion. Former detainees were sent to camps for reasons related to Islamic beliefs or practice, including working in a mosque, praying, having a prayer mat, or possessing a picture or a video with a religious theme.

Analysed in concert with other testimonial and documentary evidence gathered by journalists and other organizations, the testimonial evidence Amnesty International has gathered demonstrates that members of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang were often detained on the basis of what can only be considered “guilt by association”. Many were interned as a result of their relationships, or perceived or alleged relationships, with family, friends, or community members – many, if not most, of whom were themselves not guilty of any internationally recognized criminal offence.

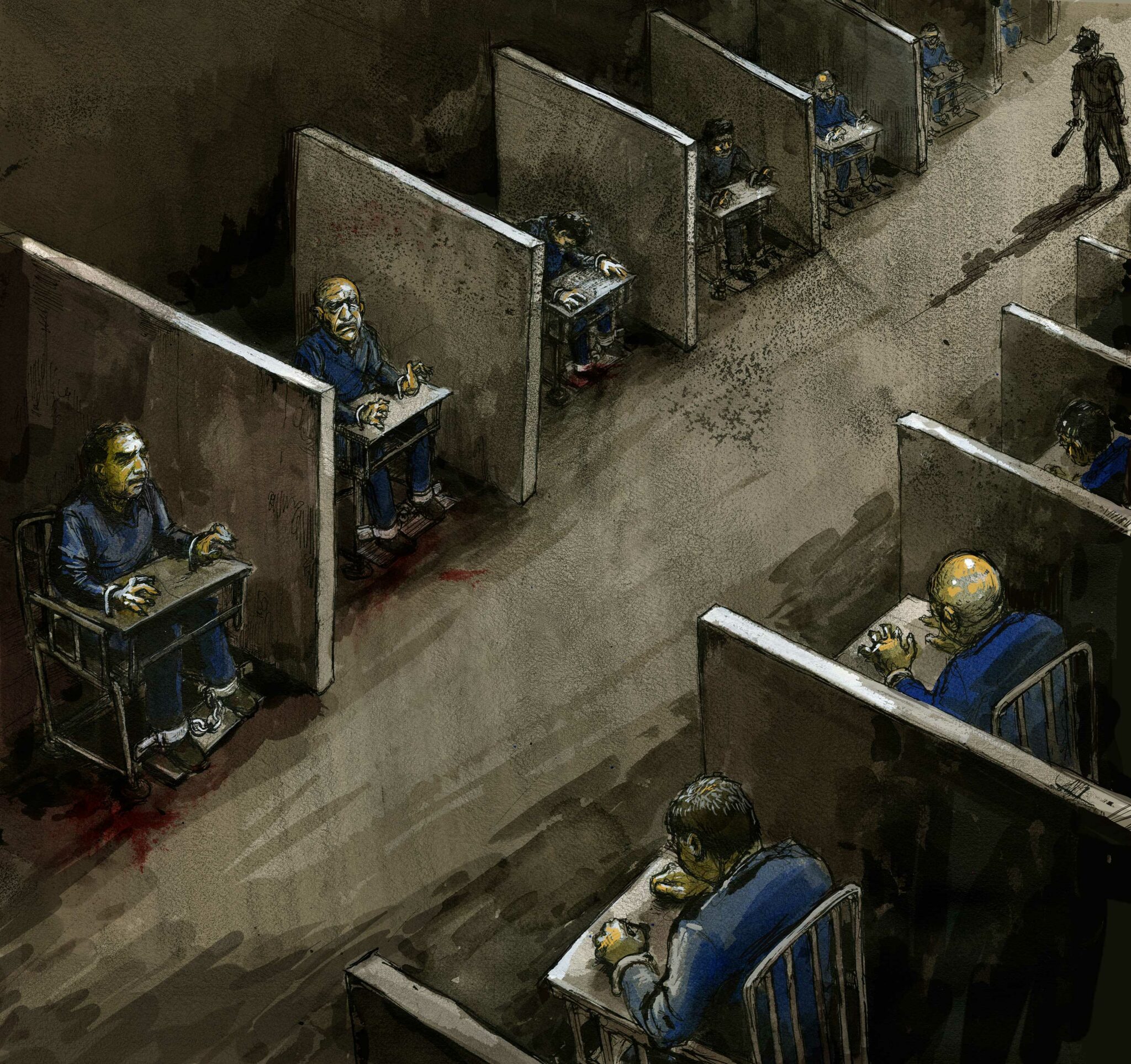

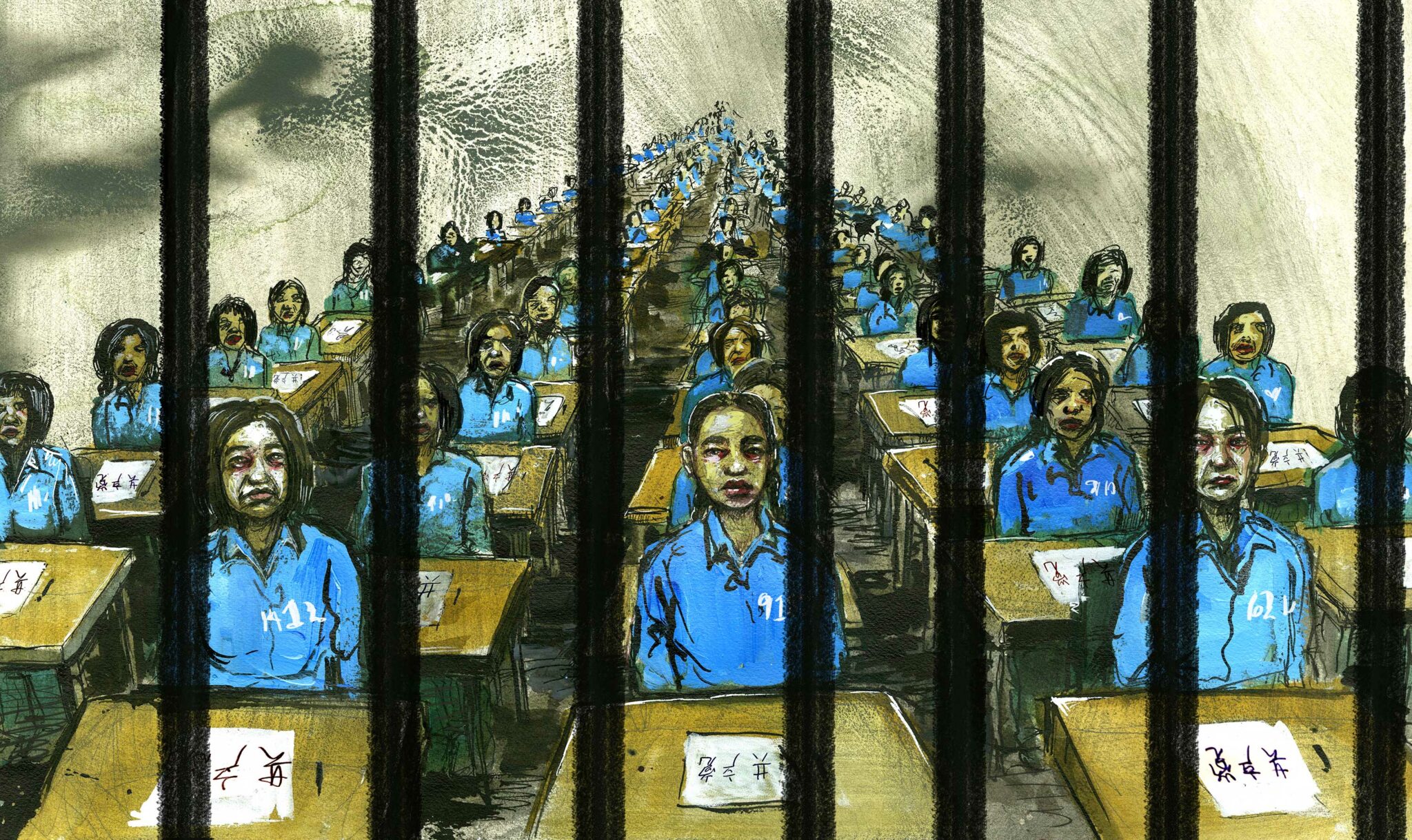

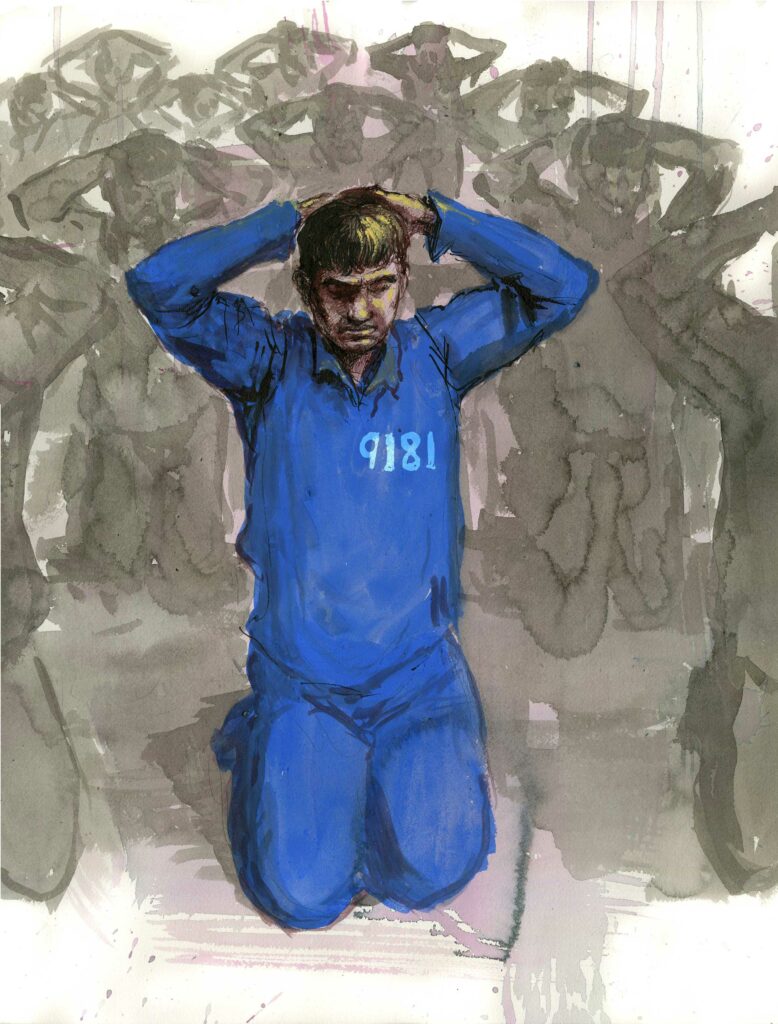

In internment camps, all detainees were subjected to a ceaseless indoctrination campaign as well as physical and psychological torture and other forms of ill-treatment. From the moment they entered a camp, detainees’ lives were extraordinarily regimented. They were stripped of their personal autonomy, with every aspect of their lives being dictated to them. Detainees who deviated from the conduct prescribed by camp authorities – even in the most seemingly innocuous ways – were reprimanded and regularly physically punished, often along with their cellmates.

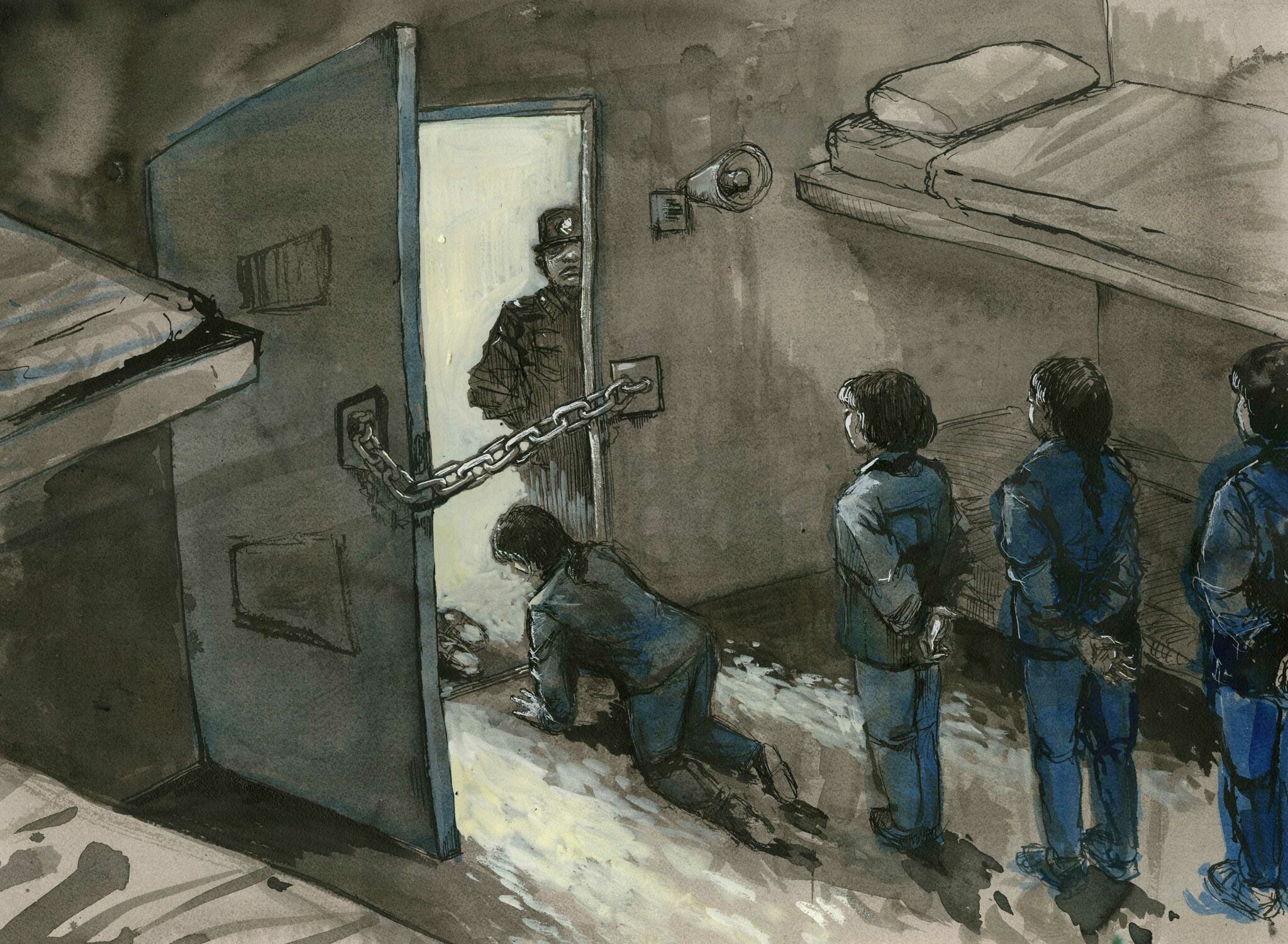

Detainees had no privacy. They were monitored at all times, including when they ate, slept, and used the toilet. They were forbidden to talk freely with other detainees. When detainees were permitted to speak – to other detainees, guards, or teachers – they were required to speak in Mandarin Chinese, a language many of them, especially older people and those from more rural areas in Xinjiang, did not speak or understand. Detainees were physically punished if they spoke in a language other than Mandarin.

There was insufficient food, water, exercise, healthcare, sanitary and hygienic conditions, fresh air, and exposure to natural light. Detainees had draconian restrictions placed on their ability to urinate and defecate. All detainees were required to “work” one- or two-hour shifts monitoring their cellmates every night. Many former detainees reported that during the first few days, weeks, or sometimes months after arriving at the internment camps, they were forced to do nothing but sit still – often in terribly uncomfortable positions – for nearly the entire day.

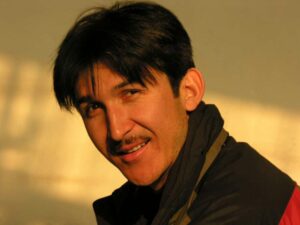

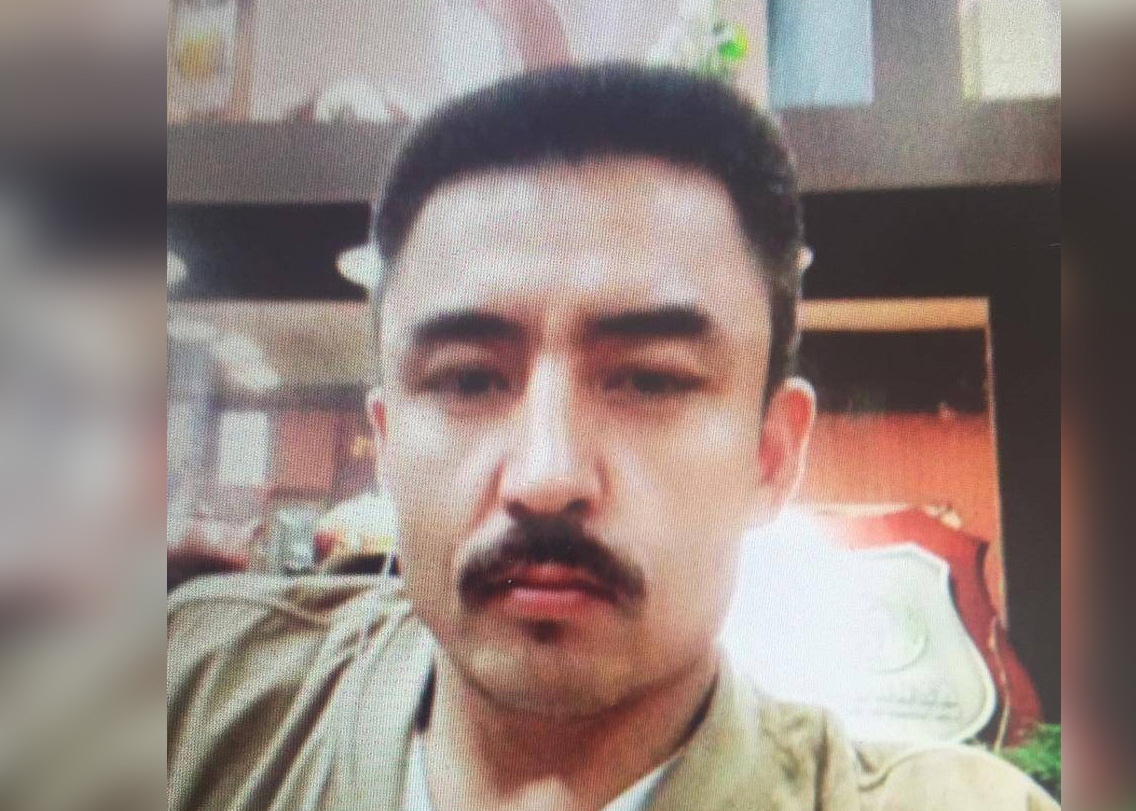

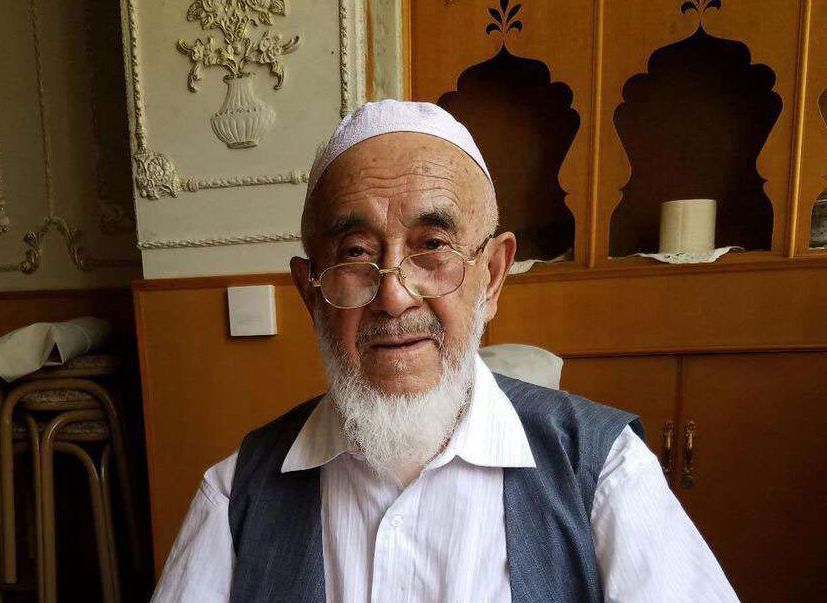

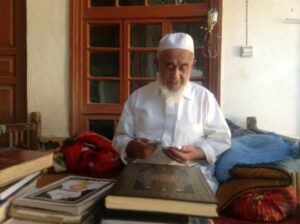

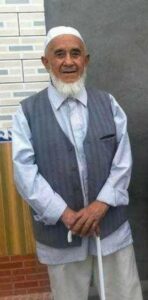

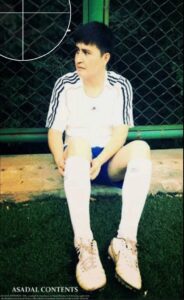

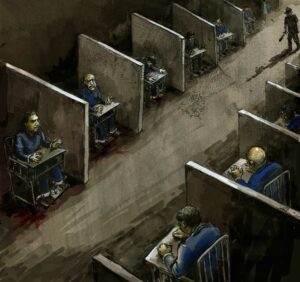

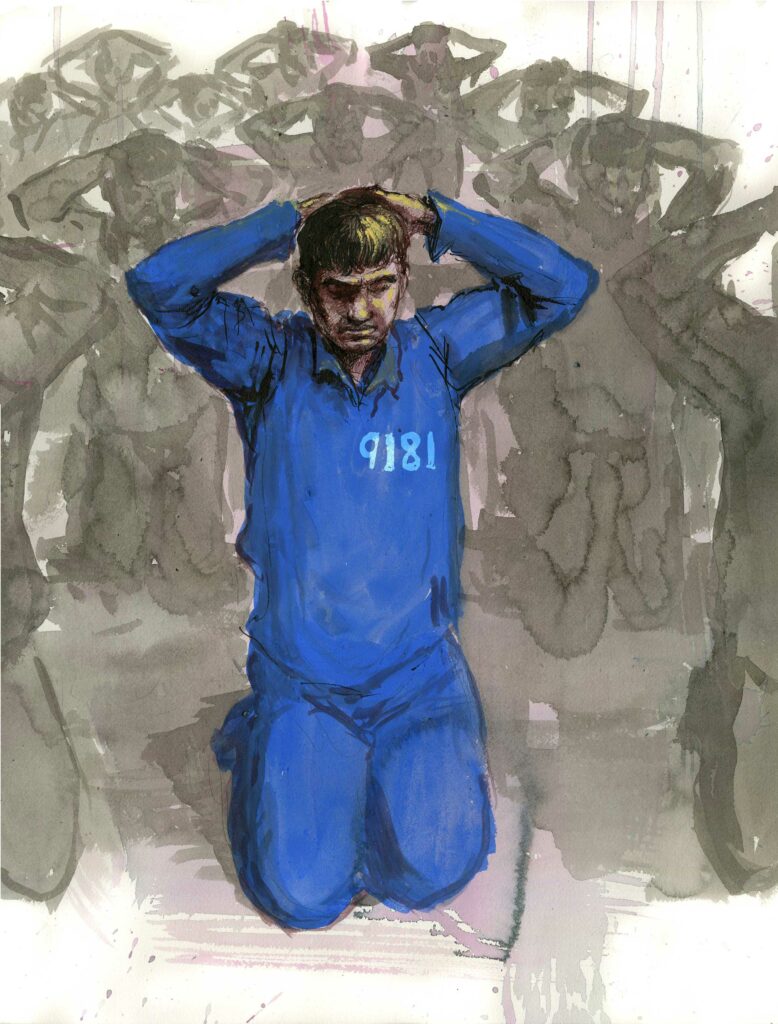

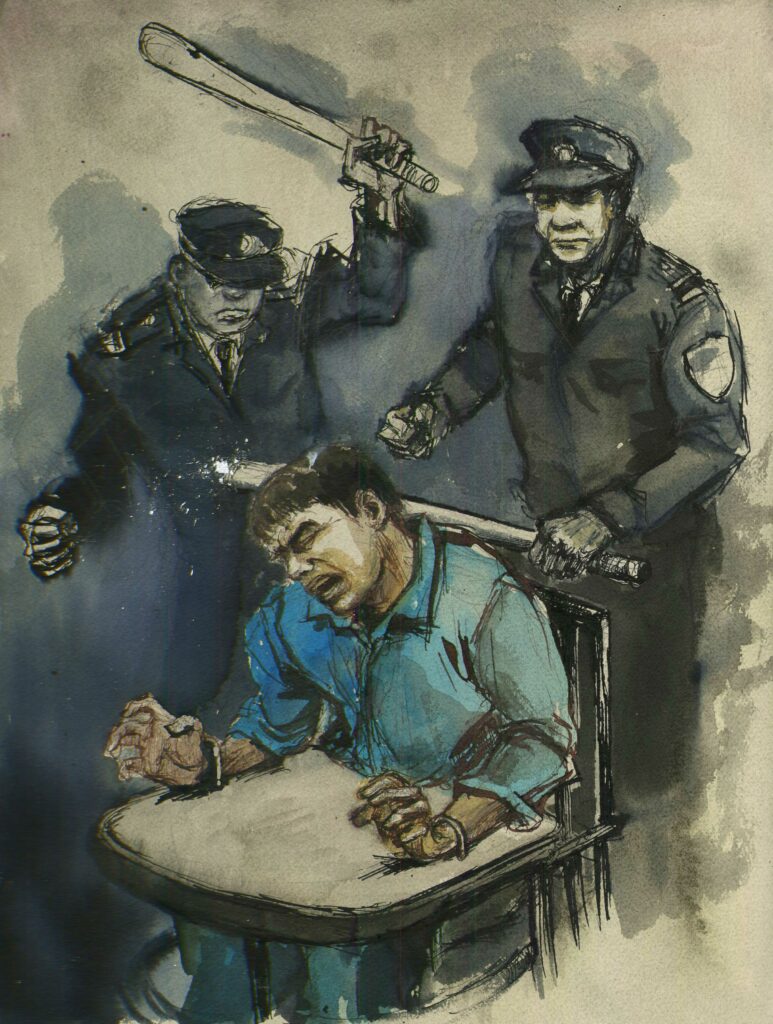

A detainee at an internment camp.

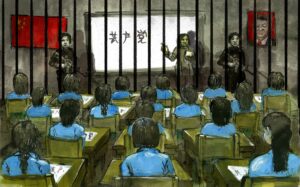

At some point after arriving nearly all detainees were subjected to highly regimented classes. The typical schedule included three or four hours of classes after breakfast. Then detainees had lunch and a short “rest”, which often involved sitting still on a stool or with their heads still on their desks. After lunch there was another three or four hours of classes and then dinner, followed by a few hours to sit or kneel on a stool and silently “review” the day’s material or to watch more “educational” videos. At nearly all times during classes, detainees were required to look straight ahead and not to speak with their classmates. Classes often involved memorizing and reciting “red” songs – that is, revolutionary songs that praise the CCP and the People’s Republic of China.

Teaching Chinese was a primary objective of the “education” that detainees received in the camps. In addition to language classes, most former detainees reported attending some combination of history, law, and ideology classes or, as many former detainees referred to it, “political education”. These classes focused largely on forcibly indoctrinating detainees about the “evils” of Islam and about how prosperous, powerful, and “benevolent” China, the CCP, and President Xi Jinping are. Yerulan, a former detainee, told Amnesty he believed the political education classes were structured to prevent detainees from having and practising their religion:

I think the purpose [of the classes] was to destroy our religion and to assimilate us… They said that we couldn’t say ‘as-salamu alaykum’ and that if we were asked what our ethnicity was we should say ‘Chinese’… They said that you could not go to Friday prayers… And that it was not Allah who gave you all, it was Xi Jinping. You must not thank Allah; you must thank Xi Jinping for everything.

Detainees were questioned or interrogated regularly. They were also frequently required to write letters of “confession” or “self-criticism”. In addition to confessing one’s “crimes”, self-criticism entailed describing in writing what the detainee had done wrong, explaining that the education they were receiving enabled them to recognize the error of their ways and “transform” their thinking, expressing gratitude to the government for this education, and promising not to return to their old habits.

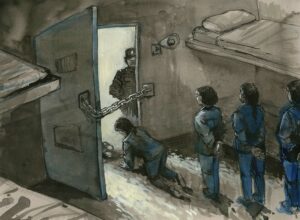

Every former camp detainee Amnesty International interviewed was tortured or subjected to other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment (in this report referred to as “torture or other ill-treatment”) during their internment. Torture and other ill-treatment are constitutive elements of life in the internment camps. The torture and other ill-treatment that detainees experience in the camps fall into two broad categories.

The first category included the physical and non-physical (that is, mental or psychological) torture and other ill-treatment experienced by all detainees as a result of the cumulative effects of daily life in the camps. The combination of these physical and non-physical measures, in conjunction with the total loss of control and personal autonomy in the camps, is likely to cause mental and physical suffering severe enough to constitute torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

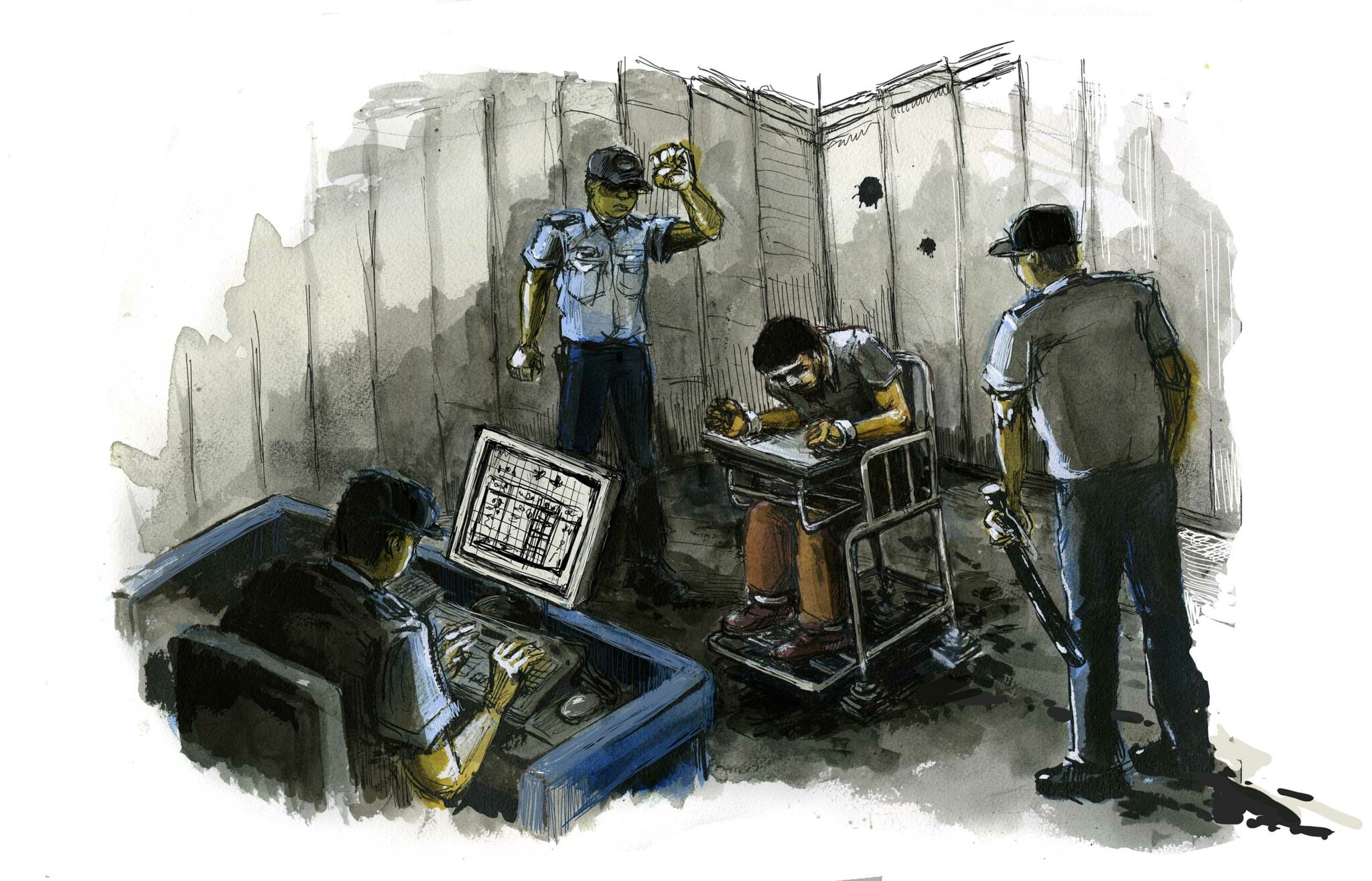

The second category of torture and other ill-treatment included physical torture and other ill-treatment that occurred during interrogations or as punishment for misbehaviour by specific detainees. Torture methods used during interrogations and as punishment included beatings, electric shocks, stress positions, the unlawful use of restraints (including being locked in a tiger chair), sleep deprivation, being hung from a wall, being subjected to extremely cold temperatures, and solitary confinement. Interrogations usually lasted an hour or more; punishments were often much longer.

Amnesty International interviewed many former detainees who were tortured or subjected to other ill-treatment during interrogations or punishments in internment camps. Amnesty also interviewed many former detainees who witnessed the torture or other ill-treatment of other detainees or who spoke with other detainees – usually their cellmates – who informed them that they had been tortured or otherwise ill-treated during interrogations or as punishment.

Former detainees described a broadly consistent pattern of treatment of detainees by staff and officials in the camps. Some of this treatment reflected patterns of torture and other ill-treatment that Chinese security forces have carried out in Xinjiang and other parts of China for decades. Mansur, a farmer, described to Amnesty how he was tortured multiple times in two camps during his time in detention – both during an interrogation and during multiple punishment sessions. He described his interrogation session:

Two guards took me from the cell and dropped me off [at the room where I was interrogated]. Two men were inside… [They asked what I did in Kazakhstan,] ‘Did you pray there? What do your parents do?’ I said I only stayed with family, that I took care of livestock, and that I didn’t do anything illegal… they asked me about mosque and praying… If I told them I had been praying, I had heard that I would get sentenced for 20 or 25 years. So I told them I never prayed. Then they became upset. They said, ‘All that time with livestock, you became an animal too!’ Then they hit me with a chair until it broke… I fell to the floor. I almost fainted… Then they put me on the chair again. They said, ‘this guy hasn’t changed yet, he needs to stay [in the camp] longer’.

Amnesty International documented one account of a death in an internment camp caused by torture. Madi told Amnesty he witnessed the torture of a cellmate who he later learned died from the effects of the torture. Madi said the man was made to sit in a tiger chair in the middle of their cell. The cellmates were made to watch him sit there, restrained and immobilized, for three days, and were expressly forbidden to help him.

[The man] was in our room for more than two months… he was made to sit in a tiger chair. [I think the man was being punished for pushing a guard.]… They brought the chair into our room… They told us that if we helped him then we would sit in the chair… It was an iron chair… his arms were cuffed and chained. Legs were chained as well. His body was tied to the back of the chair… Two [cuffs] were locked around his wrists and legs… A rubber thing attached to the ribs to make the person [sit] up straight… at some point we could see his testicles. He would [urinate and defecate] in the chair. He was in the chair for three nights… He died after he [was taken out of the cell]. We found out through [people] in the cell.

Most of the detainees interviewed by Amnesty were in the camps for between nine and 18 months. The process to determine whether detainees were released from camps and sent home is not well understood, including by many detainees. Like the process surrounding the initial detention and transfer to the internment camp, much of the release process appeared to operate outside the scope of the Chinese criminal justice system or other domestic law. There was a total absence of any transparent criteria or legal assistance and protection. Nothing that former detainees experienced during the time leading up to their release indicated any regard for the fairness and due process required by the gravity of deciding individuals’ fates. Detainees who were released were forced to sign a document that forbade them from speaking with anybody – especially journalists and foreign nationals – about what they experienced in the camp. Former detainees were informed that they would be interned again if they violated this prohibition, as would members of their families.

After being released from internment camps to go home, former detainees faced further severe restrictions on their human rights, particularly their freedom of movement. These restrictions were in addition to the discriminatory policies directed at all members of ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang. Nearly all former detainees who spoke to Amnesty were required to continue their “education” and to attend classes in Chinese language and political ideology after they were released. They were also forced to publicly “confess” their “crimes” at flag-raising ceremonies.

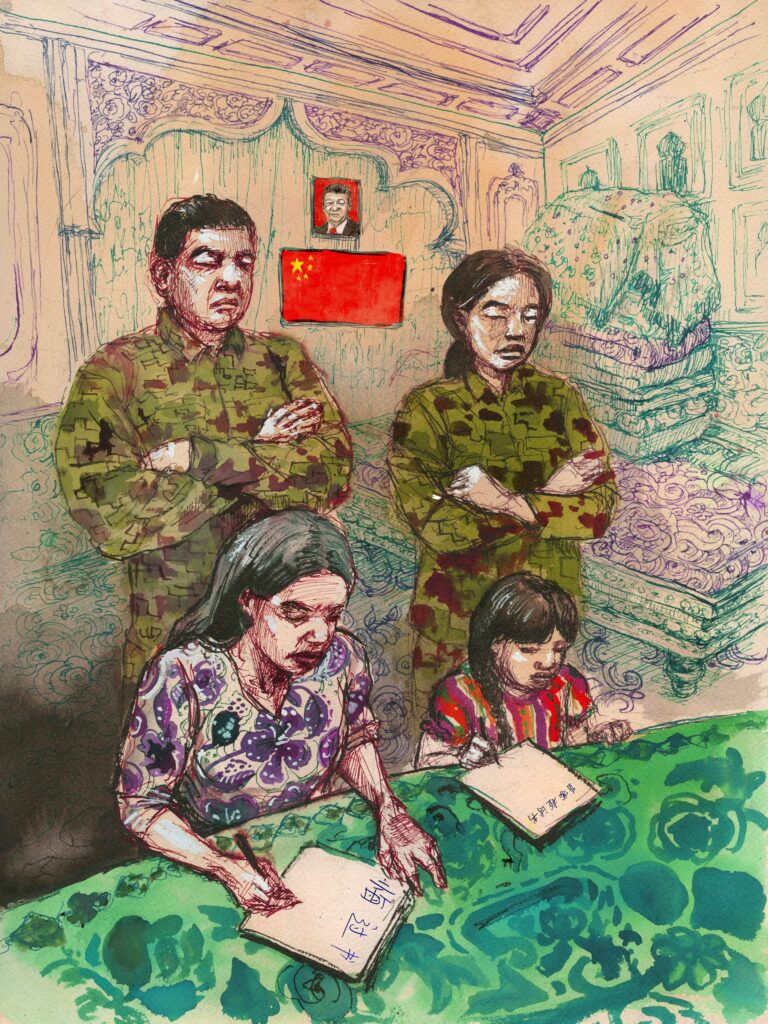

All former detainees Amnesty International interviewed said they were placed under both electronic and in-person surveillance and subjected to regular evaluations from government employees and cadres. Nearly all former detainees reported that government employees or cadres were required to stay with them in their homes for several nights per month after they were released from a camp. For at least several months, nearly all were prohibited from leaving their village or township. If they were allowed to leave, they were required to get written permission from the authorities beforehand.

Amnesty interviewed former detainees who were sent from the camps to work in factories. Arzu told Amnesty that after spending six months in one camp he was transferred to another camp, where he was taught to sew in preparation for being sent to a factory. He was then required to live and work in a factory for several months making government uniforms. These testimonies point to a number of ways in which the authorities in Xinjiang appear to be forcing or compelling Uyghurs and other members of ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang to engage in certain types of labour, sometimes as an extension of the “education” received in the camps.

Some detainees were reportedly transferred from camps to prisons. Like the process of being released to go home, the seemingly related process through which camp detainees were given prison sentences is not well understood. It is also unclear how the release process and the sentencing process were connected – especially how, or if, the prison sentencing process in the camps was integrated with any formal sentencing process outside the camps.

Amnesty International was not able to interview anyone who was given a prison sentence in a camp and then sent to a prison. Amnesty did, however, interview former camp detainees who said they were given sentences that were subsequently “forgiven”. Amnesty also interviewed former detainees who said that while they were detained, one or more of the people in their classes received prison sentences, often apparently for everyday behaviour far removed from any type of recognized offence. Many of the former detainees personally knew other people – usually multiple people – who had been given prison sentences.

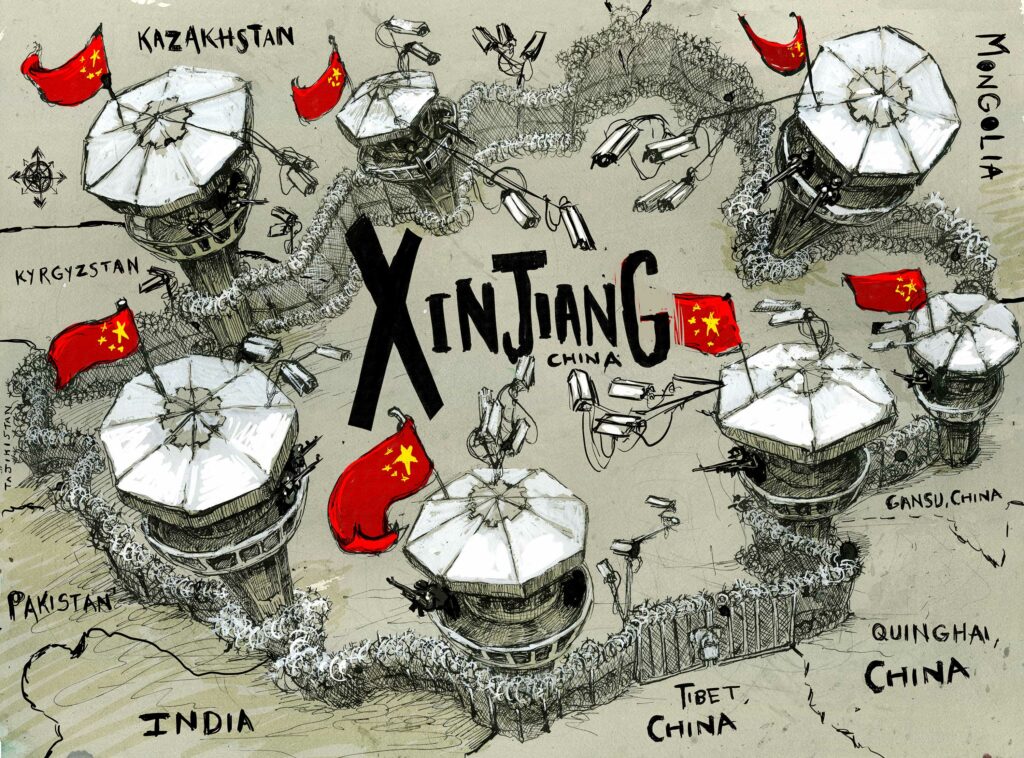

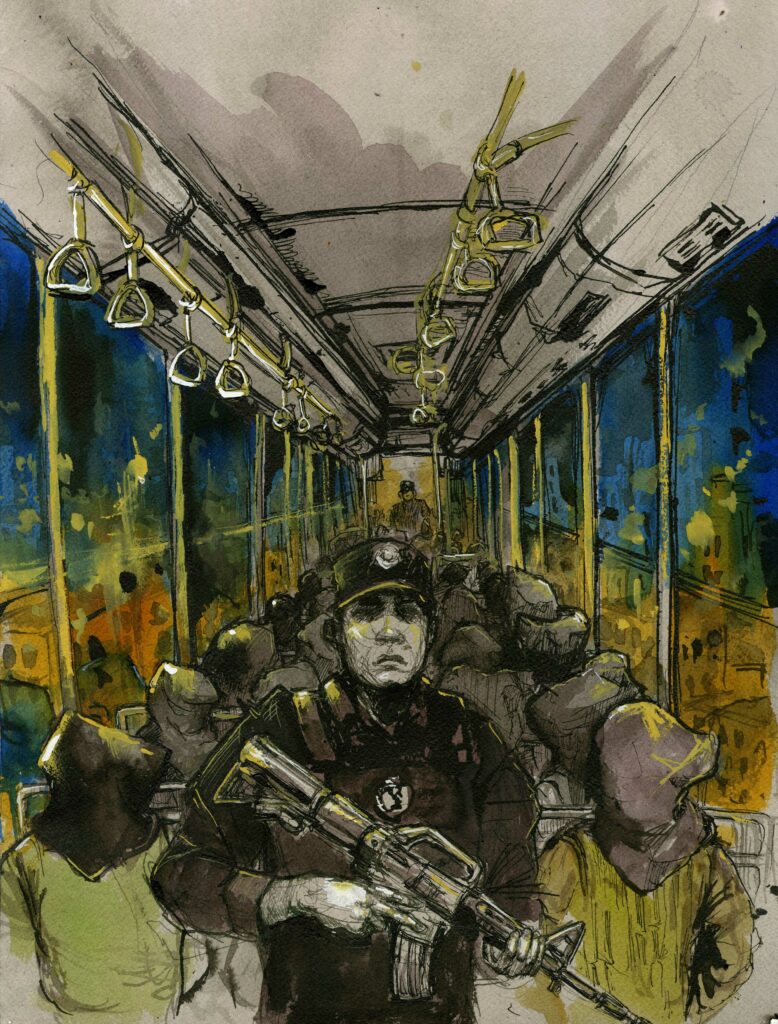

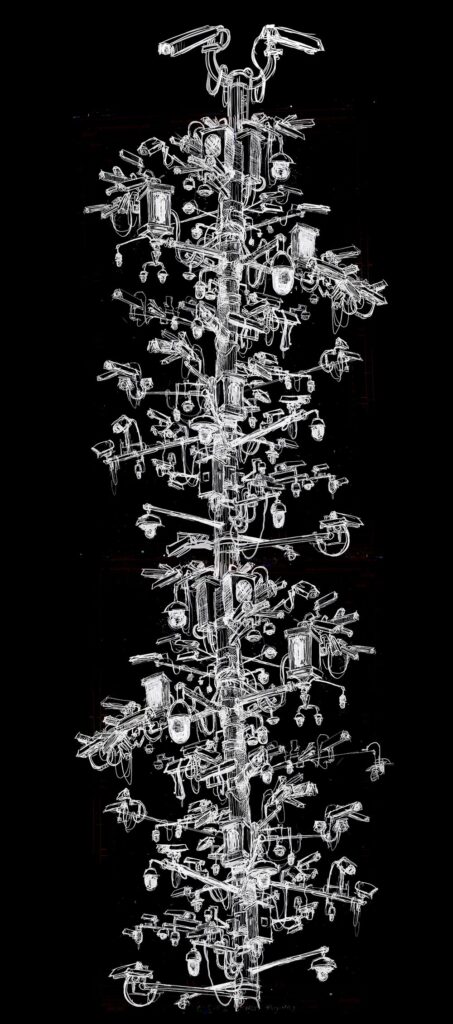

The government of China has enacted other far-reaching policies that severely restrict behaviour of all members of predominately Muslim ethnic groups, including those who have never been sent to a camp or prison. The brutal effectiveness and tremendous scale of the government’s campaign derive from the government’s unprecedented use of surveillance technology, coupled with its ability to make large portions of the region’s population help it to execute its will. The government relies on a nearly inescapable in-person and electronic surveillance operation designed to ensure that the behaviour of ethnic minority groups is continuously monitored and evaluated. Ubiquitous government cadres, violent security forces, and a non-independent legal system act in concert to conduct the surveillance and enforce rights-violating policies.

Muslims living in Xinjiang may be the most closely surveilled population in the world. The government of China has devoted tremendous resources to gathering incredibly detailed information about this group’s lives. This systemized mass surveillance is achieved through a combination of policies and practices that infringe on people’s rights to privacy and freedom of movement and expression. According to former residents of Xinjiang, the system of surveillance involves extensive, invasive in-person and electronic monitoring in the form of:

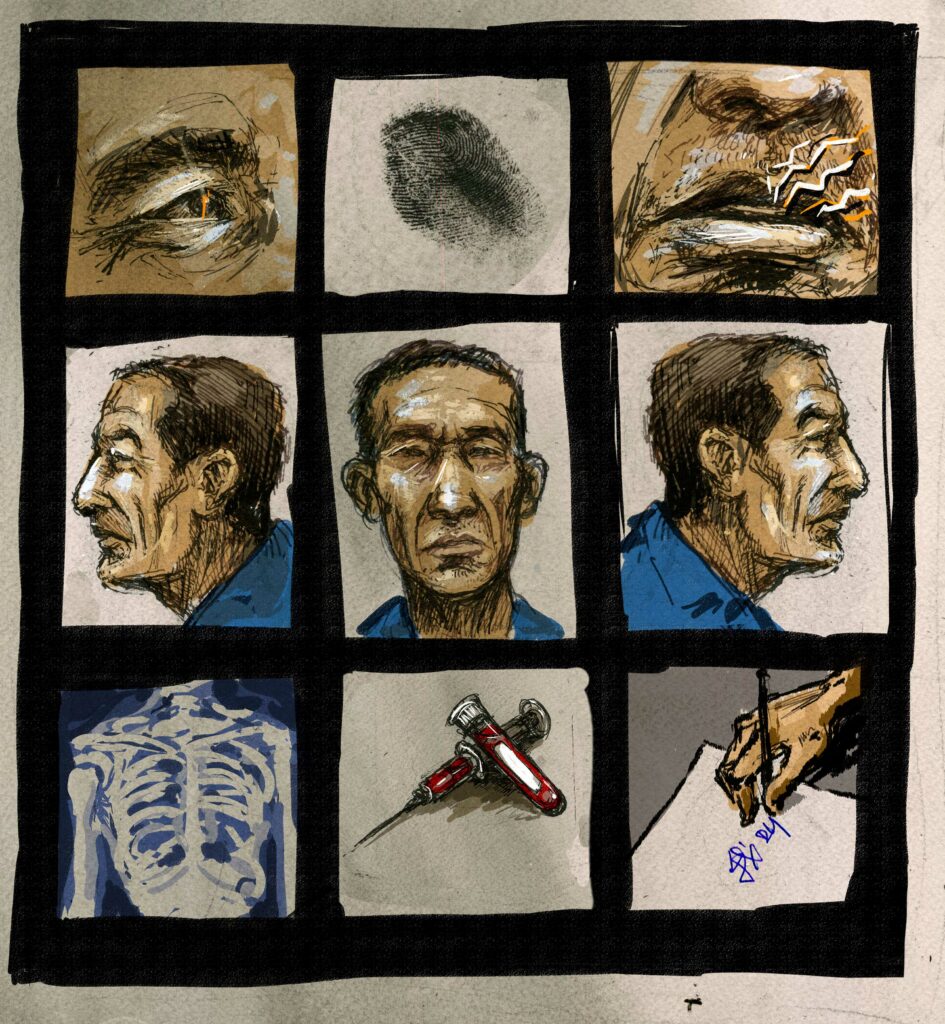

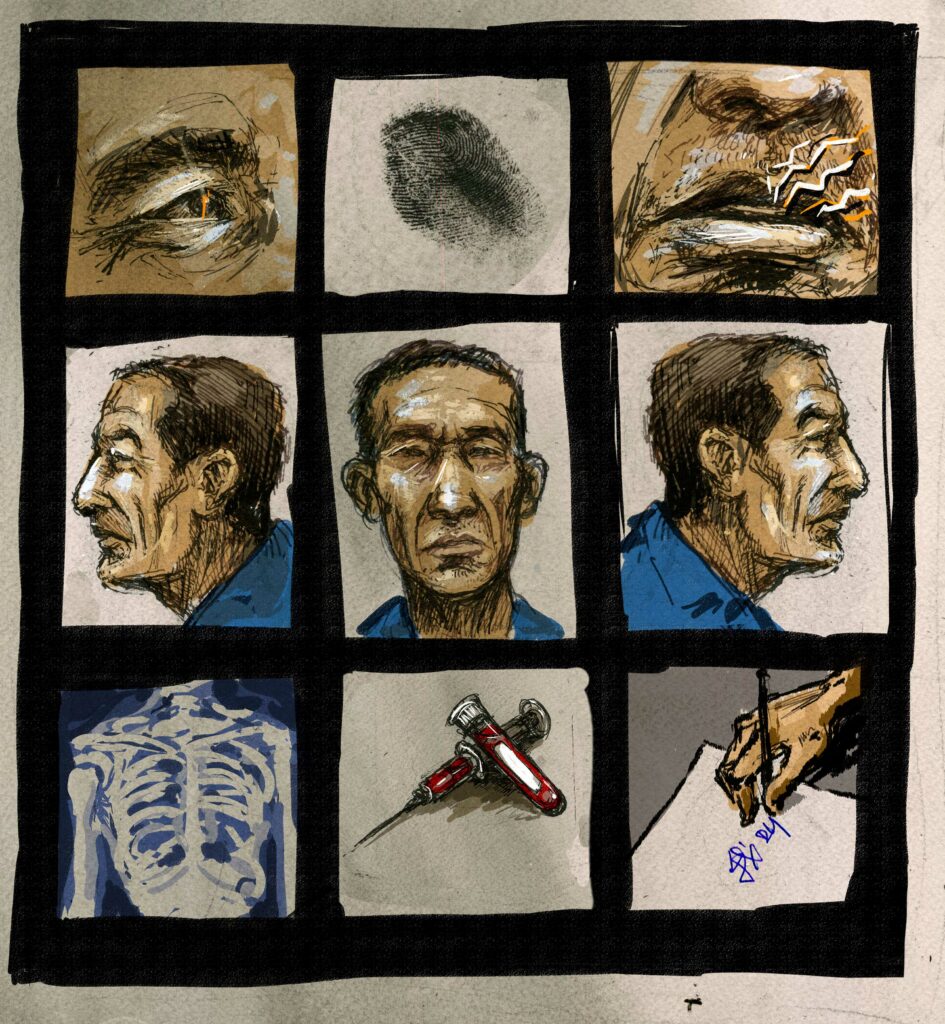

- biometric data collection, including iris scans and facial imagery;

- invasive interviews by government officials;

- regular searches and interrogations by ubiquitous security officers;

- “homestays” by government employees and cadres assigned to live with ethnic minority families;

- an ever-present network of surveillance cameras, including facial recognition cameras;

- a vast network of checkpoints known as “convenience police stations”; and

- unfettered access to people’s personal communication devices and financial history.

Chinese authorities collected detainees’ biometric data before sending them to internment camps. This included photographs, fingerprints, an iris scan, a voice recording, and a writing sample. Blood samples and X-rays were also taken.

In addition to providing the government with enormous amounts of personal information, this operation allows the authorities to comprehensively track – in real time – the communications, movements, actions, and behaviours of Xinjiang’s ethnic minority populations.

Muslims living in Xinjiang cannot move freely. The government restricts their travel both within Xinjiang and between Xinjiang and the rest of China. The government also makes it extraordinarily difficult – often impossible – for members of ethnic minority groups, particularly Uyghurs, to travel abroad. All members of ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang were forced to hand over their passports to the government in 2016 and 2017. Very few people have been able to get them back.

Former residents of Xinjiang said movement restrictions are enforced in a discriminatory manner. Interviewees said the police stopped only ethnic minorities on the street and checked their ID. Witnesses, including one who worked at a government checkpoint, reported that Han Chinese either did not need to go through the checkpoints at all or were essentially waved through without having their bodies or phones searched and without being questioned. Yin, a Han Chinese person who visited Xinjiang, told Amnesty about the discrimination they witnessed while travelling:

The surveillance cameras are literally everywhere… The discrimination is so blatant. When I boarded a train, they didn’t check anything, but the Uyghurs sitting right across from me, they checked their tickets and their phones… When I was in the station, there were two lines [for security checks], one for Uyghurs and one for Han without facial recognition, just through a metal detector. The line for Uyghurs was very long… Under a tunnel in [a major city] I just walked by, but Uyghurs had to have a full body check with metal detectors, including old men. They were checked at both sides of the tunnel. I was carrying luggage, and no one even checked my bag. I went through the [security] door, but no one checked with a wand… Because I am Han, I was not checked… I spoke with a [government official] who said, ‘Uyghurs have to be treated differently because there are no Han terrorists’.

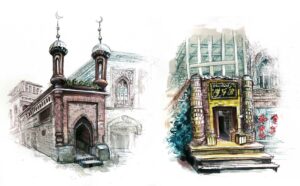

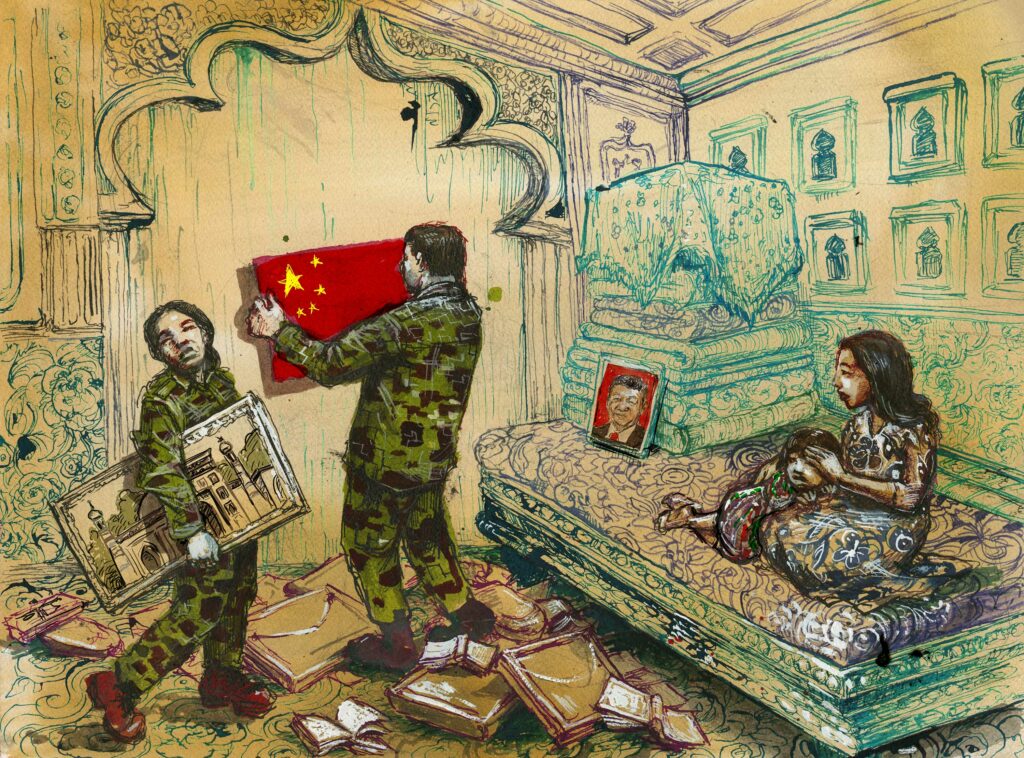

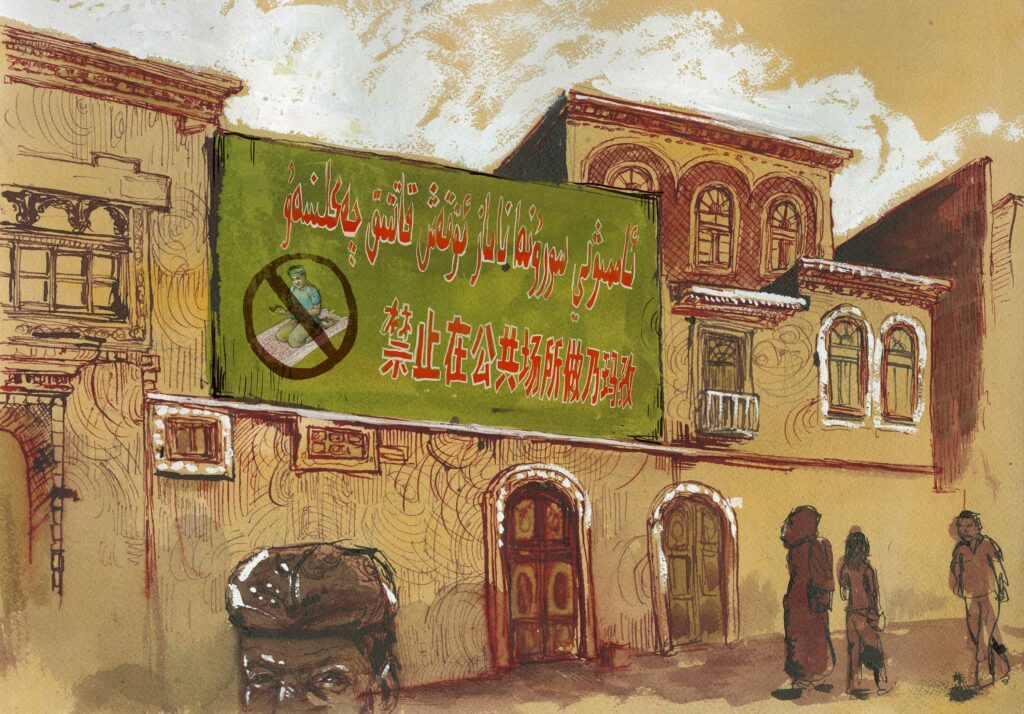

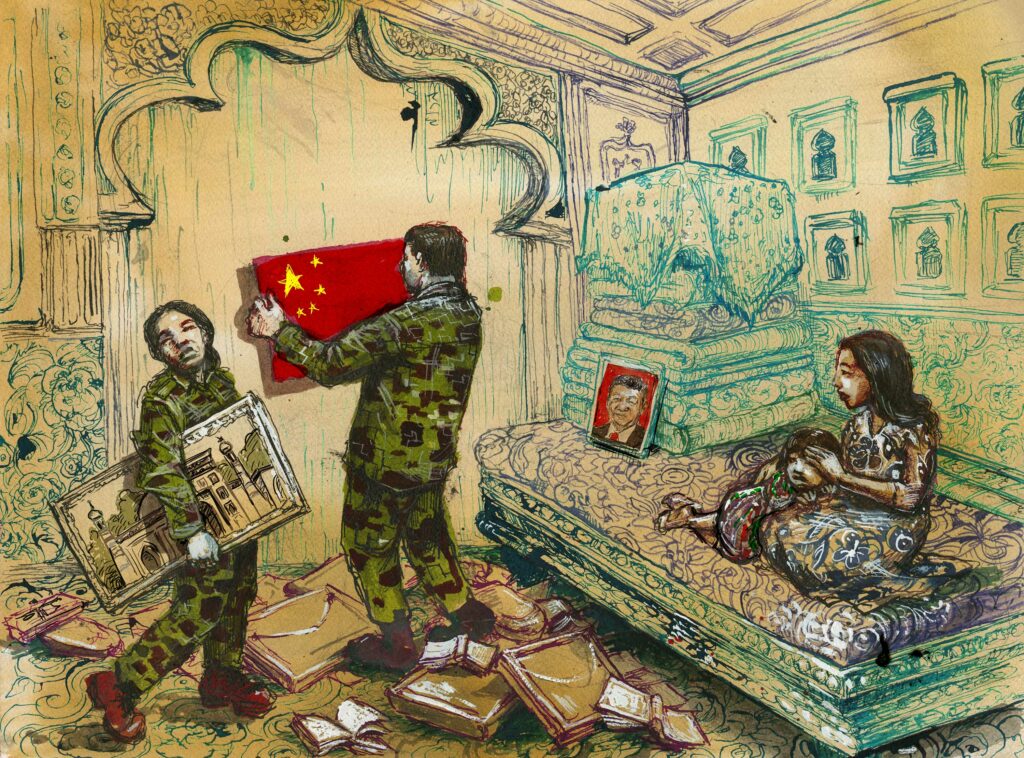

Muslims living in Xinjiang cannot practise their religion. Former detainees and other people interviewed by Amnesty International who lived in Xinjiang between 2017 and early 2021 also described an environment that was extraordinarily hostile to the practice of Islam. By the time these individuals left China, none felt comfortable displaying any signs of religious practice and all believed doing so would result in them being detained and sent to a camp. According to these witnesses, numerous Islamic practices that Muslims widely consider essential to their religion that were not explicitly prohibited by law in Xinjiang are now, in effect, prohibited. Muslims are prevented from praying, attending mosques, teaching religion, wearing religious clothing, and giving children Islamic-sounding names. As a result of the constant, credible threat of detention, Muslims in Xinjiang modified their behaviour to such an extent that they no longer displayed outward signs of religious practice.

Numerous former residents of Xinjiang told Amnesty they were forbidden to possess any religious artefacts in their houses or any religious content on their phones, including religious books, films, or photographs. Several former residents also said cultural books, artefacts, and other content associated with Turkic Muslim culture have, in effect, been banned. Aiman told Amnesty how government cadres and police barged into the houses of Muslim families and forcibly confiscated all religious artefacts:

“We went to [a part of the village] where 20 families from [a Muslim ethnic group] lived. We had to take out everything to do with religion and show them that these were illegal things… While we were doing this, we wouldn’t even knock on the door… We would just go in without asking for permission… People were crying… We gave everything to the police… We also told them to remove things written in Arabic.”

According to the evidence Amnesty International has gathered, corroborated by other reliable sources, members of predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities in Xinjiang have been subjected to an attack meeting all the contextual elements of crimes against humanity under international law. The evidence Amnesty has seen therefore provides a factual basis for the conclusion that the perpetrators, acting on behalf of the Chinese state, have carried out a widespread and systematic attack consisting of a planned, massive, organized, and systematic pattern of serious violations directed at the civilian population in Xinjiang. Amnesty International believes the evidence it has collected provides a factual basis for the conclusion that the Chinese government has committed at least the following crimes against humanity: imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law; torture; and persecution.

The government of China must immediately close all the remaining internment camps and release all persons held in internment camps or other detention facilities – including prisons – in Xinjiang, unless there is sufficient credible and admissible evidence that they have committed an internationally recognized offence. The government must also repeal or amend all laws and regulations, and end all related policies and practical measures, that impermissibly restrict the human rights of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other members of predominantly Muslim ethnic groups, including the right to freely leave and return to China and to choose and practise their religion.

An independent and effective investigation into the alleged crimes against humanity and other serious violations of human rights documented in this report is required. All those reasonably suspected of criminal responsibility should be brought to justice in fair trials. In particular, the UN Human Rights Council or the UN General Assembly must establish an independent international mechanism to investigate crimes under international law and other serious human rights violations and abuses in Xinjiang, with a view to ensuring accountability, including through the identification of suspected perpetrators.