Arbitrary detention

Since early 2017, massive numbers of men and women from predominantly Muslim ethnic groups have been detained in Xinjiang. [[[New York Times. China’s Prisons Swell After Deluge of Arrests Engulfs Muslims: Arrests, trials and prison sentences have surged in Xinjiang, where Uighurs and Kazakhs also face reeducation, 31 August 2019 →; Human Rights Watch, China: Baseless Imprisonments Surge in Xinjiang – Harsh, Unjust Sentences for Uyghurs, Other Muslims, 24 February 2021 →]]] This includes at least hundreds of thousands who have been sent to prisons as well as hundreds of thousands – perhaps 1 million or more – who have been sent to internment camps. [[[For estimates about the number of detainees in Xinjiang See Patrick deHahn, Quartz, “More than 1 million Muslims are detained in China—but how did we get that number?”, 4 July 2019 →; Jessica Batke, ChinaFile, “Where Did the One Million Figure for Detentions in Xinjiang’s Camps Come From?”, 8 January 2019 →; Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) and Equal Rights Initiative (ERI), “China: Massive Numbers of Uyghurs & Other Ethnic Minorities Forced into Re-education Programs,” August 3, 2018 →; Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), “CHRD Stands Firmly by Estimate of One Million Uyghurs Detained,” 3 August 2020 →; Adrian Zenz, “New Evidence for China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in XUAR,” China Brief, vol. 18, issue 10, May 15, 2018 →; Adrian Zenz, The Journal of Political Risk, “Wash Brains, Cleanse Hearts”: Evidence from Chinese Government Documents about the Nature and Extent of Xinjiang’s Extrajudicial Internment Campaign,” November 2019 →]]]

In 2017, many of the internment camps were in former schools and other government buildings that had been securitized and otherwise repurposed to house detainees and prevent escapes. [[[Nathan Ruser, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, “Exploring Xinjiang’s detention system: The world’ most comprehensive database – 380+ facilities,” →]]] In 2018, detainees in the initial camps were often transferred to larger facilities that had been specifically constructed as detention facilities. (For more on the closure of the camps and status of the physical infrastructure of the internment camp system, see text box “Evolution of the internment camp system and the larger system of mass incarceration in Xinjiang”.)

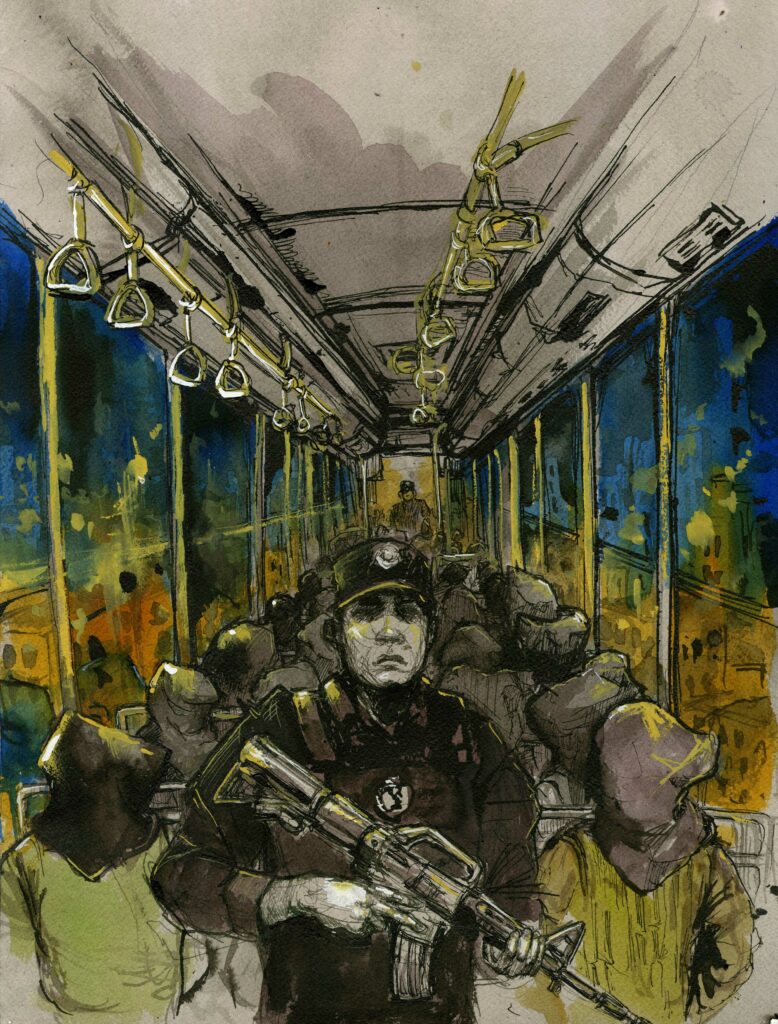

Detainees on their way to an internment camp.

Amnesty International interviewed 55 people – 39 men and 16 women – who spent time in internment camps and were later released. All of these former detainees were arbitrarily detained for what appears to be, by all reasonable standards, entirely lawful conduct; that is, without having committed any internationally recognized criminal offence. Their detention in internment camps violated numerous fundamental aspects of international human rights law. All of the detainees were denied due process during and after their initial detention. None were allowed access to legal counsel. None were provided with an arrest warrant or even a reason for their detention that included a credible allegation of a criminal offence recognized under international law. [[[See also: Human Rights Watch, “Free Xinjiang ‘Political Education’ Detainees: Muslim Minorities Held for Months in Unlawful Facilities,” 10 September 2017 →; Chinese Human Rights Defenders, “Criminal Arrests in Xinjiang Account for 21% of China’s Total in 2017: China’s Counter-Terror Campaign Indiscriminately Targets Ethnic & Religious Minorities in Xinjiang,” 25 July 2018 →]]]

The internment camp detention process appears to be operating outside the scope of the Chinese criminal justice system or other known domestic law. According to government documents and statements by government officials, applying criminal procedure would be inappropriate because the camps are not detention facilities and the people in the camps are there “voluntarily” and are not criminals. The government has publicly claimed that these facilities – which it refers to as “vocational training” or “transformation-through-education” centres – were set up as part of a national poverty alleviation programme or a deradicalization programme. Government cadres have been instructed to inform family members of people detained in camps that the detainees were not criminals. [[[The Xinjiang Papers: Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “’Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims: More than 400 pages of internal Chinese documents expose an unprecedented inside look at the crackdown on ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region.”, New York Times, 16 November 2019 →]]] In March 2019, Shohrat Zakir, governor of Xinjiang, described the camps as “boarding schools” and in December 2019, indicated that attendance in the camps was voluntary, saying “attendees are free to join or quit programmes at any time.” [[[Xinhua News, “Trainees in Xinjiang education, training program have all graduated: official”, 9 December 2019 →]]]

Contrary to the government’s public statements, leaked government documents refer to people sent to these facilities as being “punished”. [[[Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, New York Times, New York Times, “Document: What Chinese Officials Told Children Whose Families Were Put in Camps,” 16 November 2019 →]]] As demonstrated by the testimonies and other evidence below, attendance in the camps is not voluntary, and conditions in the camps are an affront to human dignity.