The process of being released from an internment camp

The process to determine whether detainees are released from camps is not well understood, including by many detainees. Like the process surrounding the initial detention and transfer to the internment camp, much of the release process appears to be operating outside of the scope of the Chinese criminal justice system or other domestic law. There is a total absence of any transparent criteria or legal assistance and protection. Nothing that former detainees experienced during the time leading up to their release indicates any regard for the fairness and due process required by the gravity of deciding individuals’ fates.

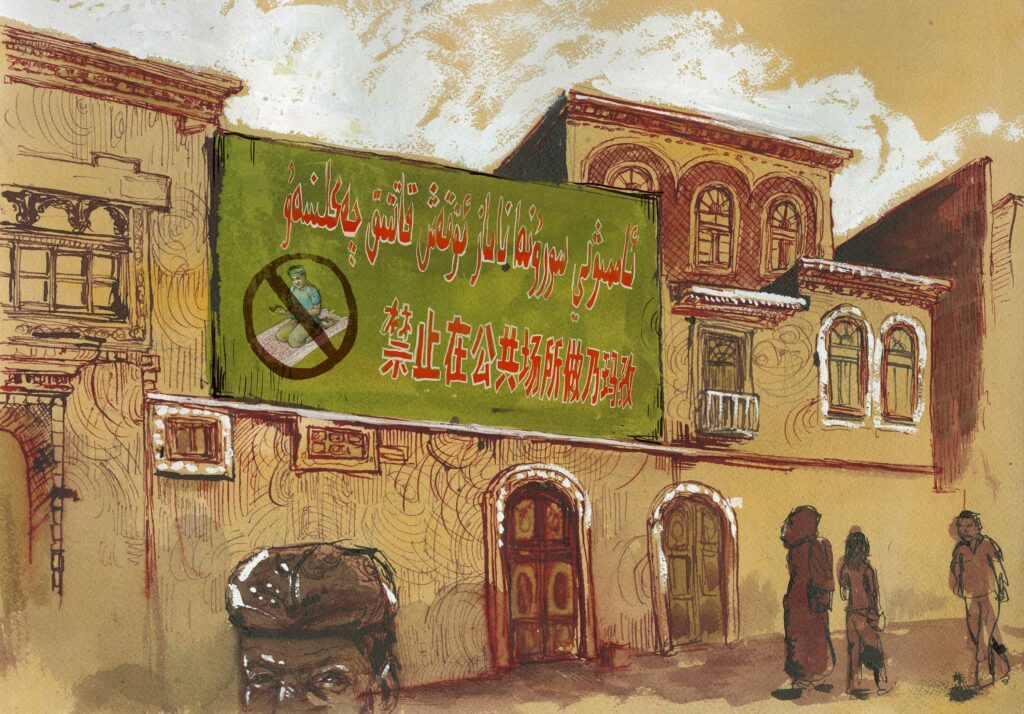

A billboard stating that ‘Praying in public places is strictly forbidden’. Signs with this phrase have been documented in Xinjiang.

Leaked Chinese government documents, particularly the Telegram, provide some insight into how the government intended – at least at one point – the release process to work. [[[The Telegram (previously cited), para 17.]]] Based on testimony from former detainees and witnesses and on what we know from the Telegram, the decision to release or transfer someone is essentially the culmination of a process that begins when an individual is first detained. From that moment, there is an ongoing process of monitoring and evaluation, whereby people are given scores. A detainee’s behaviour reportedly affects their score, which factors into the release determination.

According to the Telegram, once a detainee arrives at an internment camp there are five broad criteria that must be met to be designated as ready to be considered for release from the camp. The detainee must have

- been placed in the normal management group;

- been in the camp for at least a year;

- displayed some form of improvement with respect to their “problem” since arriving in the camp;

- achieved adequate scores with respect to “ideological transformation, academic achievement, compliance and discipline, etc.”; and

- no “other circumstances that affect completion”.

Once these criteria are met, a detainee can proceed to the first of several additional evaluations undertaken by camp and other government officials. First, “a student evaluation team overseen by the Party organization secretary” undertakes a “preliminary” evaluation and then checks the Integrated Joint Operations Platform to see if it has flagged any “new problems”. Then, in the absence of any new issues flagged by IJOP, the case is reported “up level-by-level” to three different groups of government cadres, the last of which is the “local (prefecture or city) vocational skills education and training service bureau” that, in concert with “comrades of the local [Party] committee”, makes the final determination about whether the detainee is ready for “completion” and ultimately release. [[[The Telegram (previously cited), para. 18.]]]

It is also plausible that the decisions to release individual detainees were based on factors unrelated to the criteria described in the Telegram. According to reports from former detainees interviewed by Amnesty and other organizations, the criteria in the Telegram were not always adhered to. For example, a significant number of detainees have been released without being in a camp for a year. [[[Amnesty International interviews; See also, Xinjiang Victims Database →]]]

The decision to release a detainee is also based in part on the behaviour of the detainee’s family outside the camps, which is also being monitored, evaluated, and incorporated into the detainee’s score. A 2017 government directive on how to answer questions from ethnic minority students who wonder where their relatives are instructed cadres to tell the students that their behaviour could hurt their relatives’ scores. [[[The Xinjiang Papers: Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “’Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims: More than 400 pages of internal Chinese documents expose an unprecedented inside look at the crackdown on ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region.”, New York Times, 16 November 2019 →]]] Former detainees also said that after they were released they learned their family and friends had been questioned before their release and that their family members had to fill out a long questionnaire. [[[Amnesty International interviews.]]]

Aiman, a government cadre who assigned scores to families in her village, told Amnesty how cadres also scored family members of people in internment camps and said that family members were told that if they went to work in specific factories or attended Chinese language classes it would increase their scores. Although Aiman was personally sceptical that detainees were ever released early because of good behaviour by their family members, she was instructed to inform family that it could. Moreover, according to Aiman, when men were sent to camps, authorities would pressure their wives to work in factories:

If [a woman] refused, then they threatened that her husband’s situation would be worse… Under my supervision there were [a few dozen] women who were taken to factories like this. Many of them also had no choice because they needed the money [since their family lost income when their husband was sent to a camp camp]. [[[Amnesty International interviews.]]]

Batima, who worked in a village administration office and was responsible for looking through the files of people who had been sent to camps, explained to Amnesty how detainees were held responsible for the actions of their family members outside the camps and how family behaviour could have a negative impact on an individual’s score, which is the metric the government uses to determine who should be released:

When someone was [sent to a camp] it affected three generations of the family. For example, if parents were sent then it affected the son – he could not get a job with government or police… Also, for example, the cadres staying with [the families of people in camps] overnight had to report back to the village committee if anyone prayed. And if they found this, then the score [of the person in the camp] would be lowered… And if a person was sent to re-education camp then that person’s family had to attend classes. If they did [attend] then the family would get a good score and [the person in the camp would] get released sooner, or vice versa. We collected scores each week and sent them to re-education camps. [[[Amnesty International interviews.]]]

It is also likely that some of the releases were a consequence of a change in government policy, perhaps as a result of international pressure. Moreover, it is plausible that many of the detainees were released because of a policy change with respect to certain ethnic minority groups only – in particular, ethnic Kazakhs. Testimonial evidence from former detainees’ family members suggests that a significant portion of the ethnic Kazakh population detained in the camps has been released, particularly those with Kazakh citizenship or family ties to Kazakhstan. [[[ Gene A. Bunin, Foreign Policy. “Detainees Are Trickling Out of Xinjiang’s Camps: House arrest or forced labor awaits most of those released so far in what may be a public relations ploy,” 18 January 2019 →]]] Numerous former detainees Amnesty interviewed said many other Kazakh detainees who were in their camps were released around the same time they were released. Daulet, who said he was detained for an offence related to religion, told Amnesty that nearly all the Kazakh people were released from his camp: “I was one of the last [Kazakhs] in the camp.” [[[Amnesty International interviews.]]] Many of the former detainees interviewed by Amnesty believe they were released because of public pressure on the government of China to release some ethnic Kazakh detainees. [[[See also: Reid Standish, Aigerim Toleukhanova, Foreign Policy, “Kazakhs Won’t Be Silenced on China’s Internment Camps: Activists are speaking out for those imprisoned in Xinjiang – even if their own government doesn’t like it,” 4 March 2019 →]]] The government of Kazakhstan has also reportedly engaged in closed-door diplomacy to pressure China to released ethnic Kazakhs from the camps. [[[See Catherine Putz, The Diplomat, “Carefully Kazakhstan Confronts China About Kazakhs in Xinjiang Re-Education Camps: Astana can’t afford to push Beijing too hard, even on behalf of its own citizens detained in Xinjiang Re-education camps,”14 June 2018 →; Bruce Pannier, Radio Free Europe, “Kazakhstan Confronts China Over Disappearances”, 1 June 2018 →; Qazak Times, “Consultations on the issues of Kazakh diaspora in China in continuing,” 17 November 2017 →]]]

There is dramatically less testimonial evidence about whether members of other ethnic groups – particularly Uyghurs – have been released at similar rates. But it is not known if this is because Uyghurs have not been released or because, with very few exceptions, they have been unable to travel to foreign countries where they are willing and able to speak relatively freely about their detention, or even to share information about their release. Several of the Kazakh former detainees Amnesty interview said that Uyghurs were less likely to be released than Kazakhs and the vast majority of the people they know of who were released from their camps were Kazakh, even though Uyghurs made up the overwhelming majority of the camp populations in many of those camps. [[[Amnesty International interviews.]]]